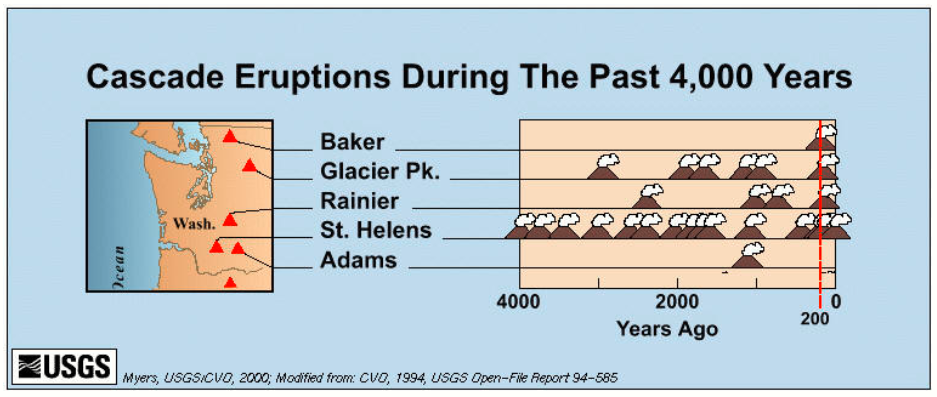

Mt St Helens is by far the most active volcano in the Pacific Northwest. Its latest eruption was in 2004, which was followed by a period of dome building which halted in early 2008.

The Mountain seems to have gotten its start just before the last ice age ended, some 10,000 years ago. The volcano was particularly restless in the mid-19th century, when it was intermittently active for at least a 26-year span from 1831 to 1857. Some scientists suspect that Mount St. Helens also was active sporadically during the three decades before 1831, including a major explosive eruption in 1800. Some of the more recent major eruptions still show their scars on the forests surrounding the still-growing mountain.

Although minor steam explosions may have occurred in 1898, 1903, and 1921, the mountain gave little or no evidence of being a volcanic hazard for more than a century after 1857. Consequently, the majority of 20th-century residents and visitors thought of Mount St. Helens not as a menace, but as a serene, beautiful mountain playground teeming with wildlife and available for leisure activities throughout the year. At the base of the volcano’s northern flank, Spirit Lake, with its clear, refreshing water and wooded shores, was especially popular as a recreational area for hiking, camping, fishing, swimming and boating. The tranquility of the Mount St. Helens region was shattered in the spring of 1980, however, when the volcano stirred from its long repose, shook, swelled, and exploded back to life.

Initial Observations

he first documented observation of Mount St. Helens by Europeans was by George Vancouver on May 19, 1792, as he was charting the inlets of Puget Sound at Point Lawton, near present-day Seattle. Vancouver did not name the mountain until October 20, 1792, when it came into view as his ship passed the mouth of the Columbia River.

A few years later, Mount St. Helens experienced a major eruption. Explorers, traders, missionaries, and ethnologists heard reports of the event from various peoples, including the Sanpoil Indians of eastern Washington and a Spokane chief who told of the effects of ash fallout. Later studies determined that the eruption occurred in 1800.

The Lewis and Clark expedition sighted the mountain from the Columbia River in 1805 and 1806 but reported no eruptive events or evidence of recent volcanism. However, their graphic descriptions of the quicksand and channel conditions at the mouth of the Sandy River near Portland, Oregon, suggest that Mount Hood had erupted within a couple decades prior to their arrival.

Meredith Gairdner, a physician at Fort Vancouver, wrote of darkness and haze during possible eruptive activity at Mount St. Helens in 1831 and 1835. He reported seeing what he called lava flows, although it is more likely he would have seen mudflows or perhaps small pyroclastic flows of incandescent rocks.

The Eruption of 1980

Psalm 104:32 – He looks at the earth and it shakes; He touches the mountains and they smoke.

I was 14, and living in Maine, when Mt St Helens blew. I was fascinated by it. I watched the buildup in the news and in the papers with fascination. I marveled along with everyone else at the display of nature’s fury. I was a paper boy at the time, and I don’t think I read and followed a story more closely. Even though I was from Maine, place names like Toutle, Castle Rock, Longview, Yakima, the Cascades quickly became familiar. It was then that I planned to live near there one day.

I joined the Army in 1983, and in early 1985, I was stationed at Ft Lewis, WA. My first weekend off, you can bet where I went… I had to see the mountain that blew its top for myself. Shortly after arriving, I was on a “volunteer” detail to help dig holes for seismic equipment. I found my favorite place.

I live in Washington State, now… and every so often I return to the Mountain to take in another dose of the grand spectacle that so completely captured my attention.

So, while unfortunately I was born on the wrong coast to be a witness to this awesome event… Here’s my summary of the events surrounding the 1980 eruption. I got most of the information from the various Welcome Centers dotting the roads leading to the Volcanic Monument, and from the USGS.

Tranquil Beauty

The mountain was, putting it mildly, beautiful. Often called “The Fuji of the West” for its slender conical shape, Mt St Helens was the Jewel of South West Washington, and a favorite getaway location for many in the area.

The mountain was, to put it mildly, beautiful. It was surrounded by old growth trees, and was fairly accessible by car. The mountain was, to put it mildly, beautiful. It was surrounded by old growth trees, and was fairly accessible by car.

The logging roads surrounding the mountain had been largely upgraded, and were open to the public. Several campgrounds were in and around Spirit Lake, and on most weekends, the area was flooded with vacationers, campers, fishermen, hikers, and others who enjoyed the pristine, outdoor environment.

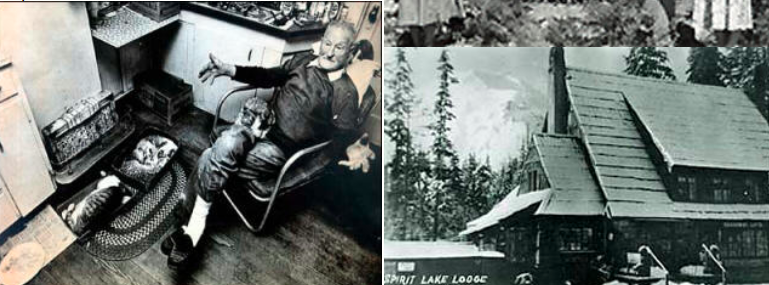

One of the highlights of the region was the lodge on Spirit Lake. It was owned by Harry Truman, who lived there since the 1930’s, and famous partly for his 16 cats.

The Lodge was a Popular Bed and Breakfast, and Harry was one of the more colorful people in the region. Sadly, he refused to leave when they ordered to evacuate…

Reawakening of a monster

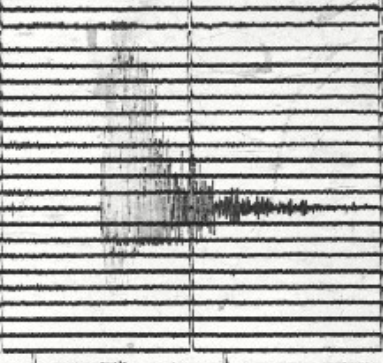

Dormant since 1857, the 123 years of silence ended when St. Helens showed her first signs of life on Thursday, March 20th with a 4.1 magnitude earthquake centered beneath the volcano. Most northwest newspapers completely ignored this earthquake because President Carter’s announcement of the Moscow Olympics boycott dominated the news.

The size of the earthquake was not that significant, but it was enough to attract the attention of the USGS… they sent a team from Vancouver to check out the mountain, and monitor things locally.

Several other earthquakes occurred, in increasing numbers.

One week later, the mountain released material, marking the first volcanic eruptions in the conterminous United States since 1914 (Lassen Peak). On March 27th, the mountain smudged the usually pristine snow at her summit with its first puff of ash. No one on the ground knew what had happened at first because the top of the mountain was encased in clouds for her first show. The small explosion left a 250 foot wide crater in the otherwise perfect cone. On March 30th there were a record 79 earthquakes recorded on the mountain.

On April 3rd, the first harmonic tremors were recorded signaling the movement of magma somewhere deep within the dome. The crater was by now 1,500 feet wide. Explosions of ash, rock and ice chunks were almost a daily occurrence by this time. The mountain had taken on an eerie, sinister look with her ash covered slopes.

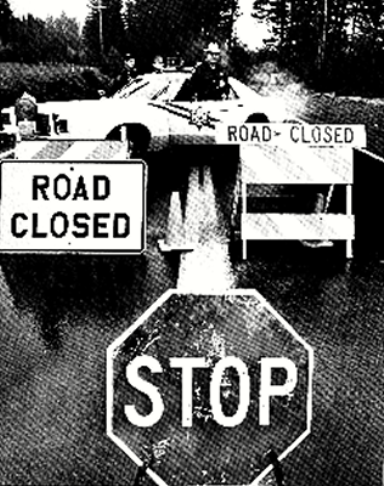

For safety reasons, “Red Zone” and a “Blue Zone” rings were mapped out around the mountain. Road blocks, like these on Route 504, were placed around the perimeter of the zones to limit traffic.

Swarms of tourists wanted to get as close as possible to the waking giant but because of the scientists inability to predict the time and magnitude of an eruption, they needed to keep people out of harms way. Despite the best efforts of local police, there were too many small logging roads that criss-crossed the area to keep out all of the curious onlookers.

For safety reasons, “Red Zone” and a “Blue Zone” rings were mapped out around the mountain. Road blocks, like these on Route 504, were placed around the perimeter of the zones to limit traffic.

Swarms of tourists wanted to get as close as possible to the waking giant but because of the scientists inability to predict the time and magnitude of an eruption, they needed to keep people out of harms way. Despite the best efforts of local police, there were too many small logging roads that criss-crossed the area to keep out all of the curious onlookers.

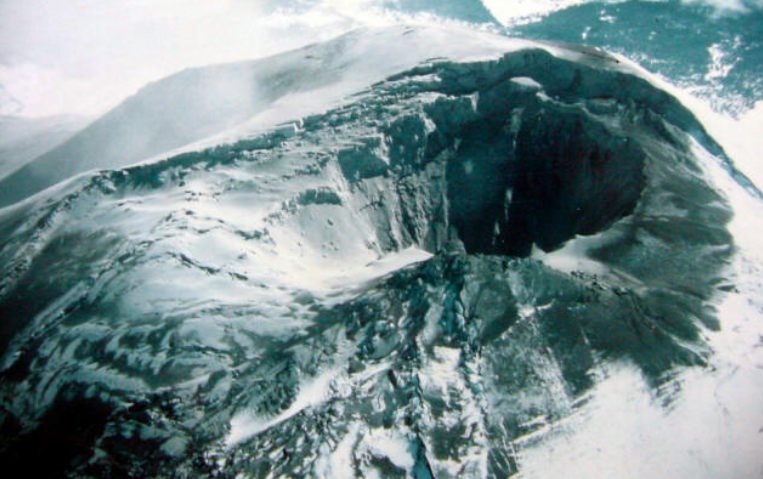

In late April a noticeable "bulge" began to form on the north face of the mountain.

In late April a noticeable “bulge” began to form on the north face of the mountain. The bulge was created by the building pressure of hot gases and magma inside the mountain. The bulge grew at an astonishing 5 feet per day.

Scientists noted that the bulge was rimmed by a huge crack, and they also commented that they didn’t know how deep the crack went into the mountain, and were concerned about long-term affects the crack would have, because it would let water leach deep into the mountain.

The bulge also had the effect of widening and deepening the crater. Warm steam, rising out of the base of the crater, melted glacial ice, and formed a lake.

On April 30th, Geologist David Johnston was sent to the new lake, to get water samples.

On May 17th, frustrated home owners living in the “Red Zone” threatened to break through roadblocks to get to their homes. A convoy of 35 home owners were escorted in by police to retrieve personal belongings from their homes and summer cabins.

Another trip into the “Red Zone” was planned for the next morning, May 18th, at 10 a.m.

Entering History

“Vancouver, Vancouver…. This is IT!”

Those are the last known words of David Johnston, who was the USGS geologist tasked with watching the Volcano Monitoring Equipment on May 18, 1980.

A magnitude 5 earthquake, deep in St Helens’s innards, touched off the largest landslide ever recorded…

With the large mass of weight removed, the pressure quickly released, and the largest explosion ever recorded blew down trees for more than 15 miles

Mt St Helens roared to life.

With the large mass of weight removed, the pressure quickly released, and the largest explosion ever recorded blew down trees for more than 15 miles to the north of the volcano. Some 20 miles beyond that, heat from the blast killed thousands of acres of trees… 240 square miles affected in all.

Nothing was ever found of David Johnston, and the ridge he was making his observations on is now named “Johnston Ridge”, in his memory.

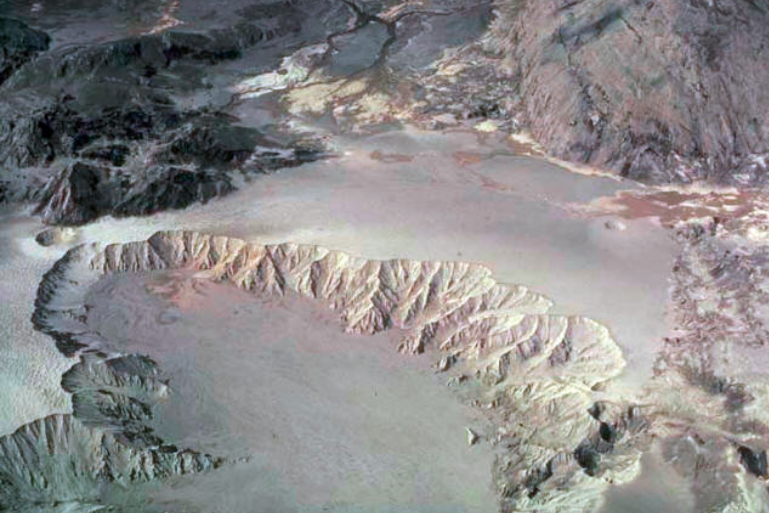

]A look at the blast zone from orbit shows just how big the affected area was… and that picture was taken about 20 years after the blast!

The mountain roared for 9 hours, dumping an incredible amount of ash in a cloud that reached 40,000 Feet, and circled the globe!

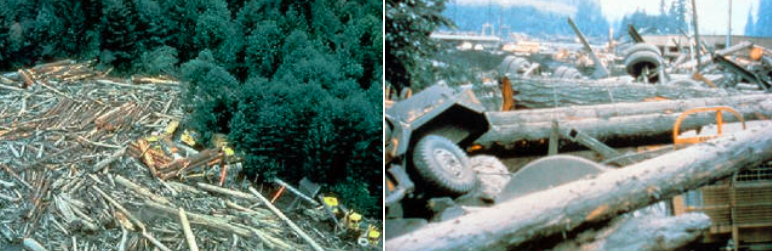

Several logging camps in the region were still operating when the blast took place, one of the exemptions to the blue and red zones being that the logging operations could continue.

Even being 10 miles away from the mountain didn’t help… the wall of ash and wind moved at about 2-300 miles an hour, carrying with it rocks, trees, hot ash, and other debris it could pick up along the way.

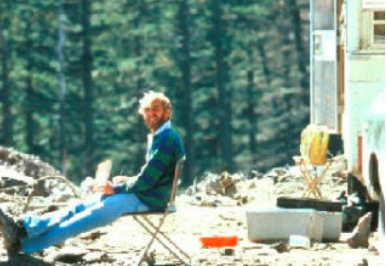

This picture of a camp was developed from a camera found in the aftermath… its owner was not found

Aftermath

The damage from the eruption was widespread. The amount of force involved in the blast is mind boggling. 1/3 of the mountain’s mass was moved in one day.

Mud, manufactured from melting glacier ice, the north face of the mountain, and countless trees swept down the Toutle River, wreaking havoc, and changing the region forever. The valley floor was left flattened, and 300 feet higher than it had been before the blast.

Several homes in the Toutle valley were transformed from a relaxing retreat to a muddy ruin. Farm land was covered over, bridges lost, and the entire region was left at a standstill for months.

Overflights of the Toutle Valley revealed a land that was almost unearthly. President Jimmy Carter described it as a “Lunar Landscape”… pilots mentioned that everything looked “black and white”.

The explosion and heat sterilized the area around the mountain… not even bacteria survived! That, and the ash, removed any and all color.

The National Guard and Medical Units from Ft Lewis scoured the area for survivors, rescuing many from the mud and ash flows.

Spirit Lake was utterly devastated by the event. All of the water of the lake was pushed up the slopes down wind of the blast, and when it swept back into the lakebed, more than 400 feet higher than it had been, it brought millions of trees, broken like twigs in the blast.

The Toutle River, and its lush valley, was quickly transformed into a frothing surge of hot mud and ash. Bridges, trees, buildings, logging equipment and more was either washed down, or buried in the valley.

Logs, cut by the lateral blast, and debris were floated in a mud that had the consistency of cement

It was the Ash, however, that everyone saw as the eruption… for several days, huge outpourings of ash occurred.

It was a lot like Snow, only it didn’t melt. No one could figure out what to do with it. You had to rinse it off your car, because brushing it was like rubbing sandpaper on it.

Snow plows were used to get it off the roadways, and folks piled it up on the low spots in their yards… eventually, it washed away from most areas.

The car to the right was 10 miles away from the volcano, burned out from the hot ash, and mired hopelessly in mud. The driver, unfortunately, was one of the 57 people who lost their lives.

Weyerhaeuser really took a hit from the eruption. They had several logging camps in and around the mountain.

Not only were large numbers of expensive equipment lost… but vast quantities of timber were lost, as well. They did harvest some of it, but many millions of board feet of timber were lost forever.

Above, you can get a sense of the scale in the pictures… the circle in the lower right shows two scientists taking readings from the ash.

Scientists, some sponsored by Weyerhaeuser, swarmed the region, gathering data.

More was learned in one day about volcanoes than had been learned in the previous 100 years.

Before and After

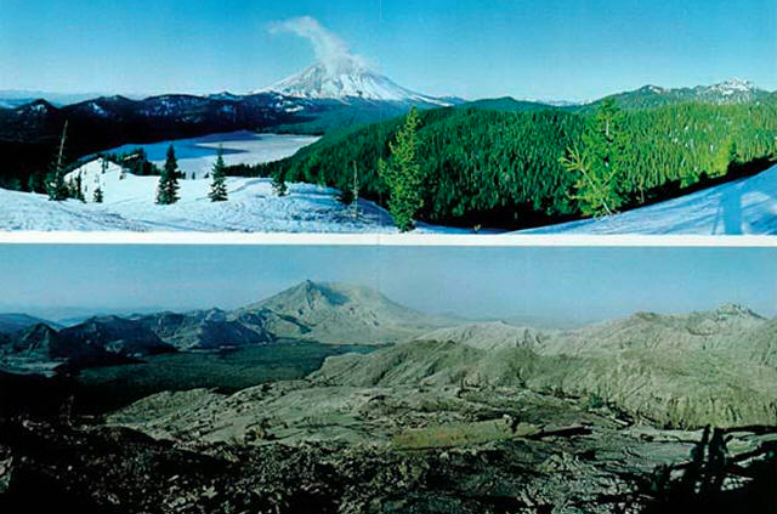

These pictures really bring home the amount of devastation that occurred in the 1980 eruption. The mountain, and the areas around it, will never be the same!

This view is a before and after, from Johnston Ridge. The left was taken the day before the blast, on May 17… the one on the right was taken in September.

This view is from Windy Ridge, above Spirit Lake. The ‘before’ was taken in December 1979. The ‘after” was taken in the summer of 1981

Below, this panoramic view of Mounts St. Helens from Mount Margaret, about 9 miles north in August 1979 and again in the summer of 1982, really emphasizes the amount of devastation caused by the mountain in the spirit lake region

Clean Up

Dredging the Columbia River quickly became a priority. Shipping lanes were clogged by silt and logs swept downstream by the Toutle and other streams in the area…

Along both sides of the river, large areas of land were created, especially in the Longview/Rainier area of the River.

In an effort to control the amount of silt moved by the streams, a large “mud dam” was built.

Route 504 needed to be rebuilt. The majority of the roadway up the valley was left under 300 feet of rubble. It was decided to run the route further up the side of the ridges along the valley.

One of the results of this was the requirement for the Hoffstadt Creek Bridge… a massive, mile long, quite impressive structure.