In South Western Washington lies one of the youngest mountains on the Cascade Mountain Range… Mt St Helens. Like most of the mountains along the Cascade Range, St Helens is a volcano, one of the most active in the world.

I’ve had the opportunity to visit this place several times, and this is a small tribute to the Mountain that has captured my imagination, and has grown to become my favorite place to be, bar none. My first trip here was in late 1984, shortly after arriving at Ft Lewis, WA. Over the years, I have returned, mostly to see the sunrise, but always have managed to see something new each time.

Mt St Helens

Long an interesting bit of scenery on the drive up or down I-5, the Mountain was a frequent stop for hikers and campers. On May 10, 1980, the mountain reawakened, and the devastation was incredible. I’ve visited there several times, and even more than 20 years after the awesome event, I still marvel at the display of power that “Mother Nature” is able to deliver in a blink of an eye… it sure makes you feel small.

The area is now known as the Mt St Helens Volcanic National Monument, and is even a more popular place to visit. It is a prime example of nature’s ability to adapt to difficulty, and is truly incredible.

Before the blast

Before the eruption,

Prior to the blast, Mt St Helens was a beautiful recreation area. Spirit Lake, at the base of the mountain, and formed by an earlier landslide may hundreds of years ago, was a popular summer destination.

This is a USGS photo of the mountain, taken in 1979… the summer before the eruption.

I took these pictures from large murals on the wall of one of the Welcome Centers along the way into the Volcanic Monument. The one above is a shot overlooking Spirit Lake. The one below the view from the Lodge at Spirit Lake, owned and operated for about 50 years by Harry Truman (not the President).

On a random day in March of 1980, that all changed. A 4.1 earthquake happened deep within the mountain, and that was followed by literally thousands of smaller quakes. Whatever plug was holding back the fire safely below was broken, and it all was heading to the surface with earnest.

Almost immediately, cracks began to form on the north slope of The Mountain, evidence that the mountain was changing its shape.

The Eruption of a Lifetime

After months of shaking and swelling, a minor 5.2 magnitude quake touched off the most massive landslide in recorded history. The entire North face of the mountain fell into the valley below, which released millions of pounds of pressure from the throat of the volcano, and Mt St Helens Roared to life.

The scale of the destruction was beyond incredible. This shot, taken by a logging crew 13 miles away from the Mountain, shows the explosion overrunning the camp as they were leaving, mere minutes after the initial blast. They actually did not make it, but this picture was found on a camera in their truck.

Two views from the same ridge

I took the second picture in 2001 from the same place they said the first picture, on display at the welcome center, was taken… I went tot he spot and took a picture from there, and then lined them up.… its VERY different! This will take a while to load, but its worth it!

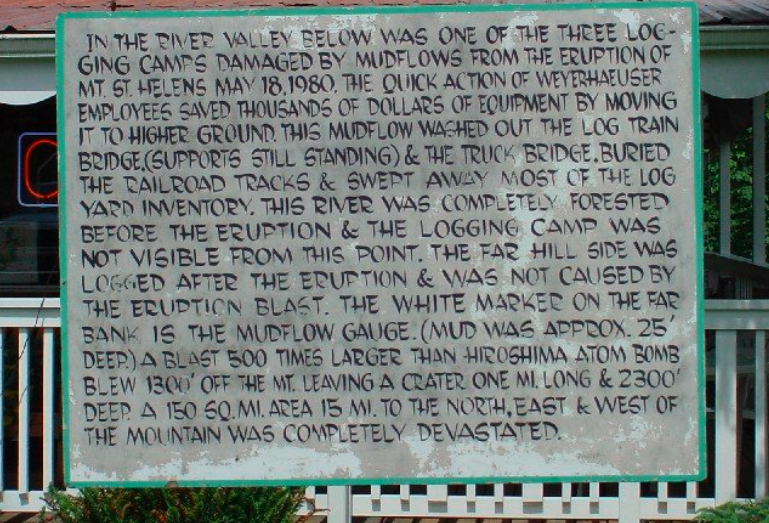

This sign, at a restaurant above the site of the logging camp above, really brings home the importance the locals place on the mountain, and the day it became famous.

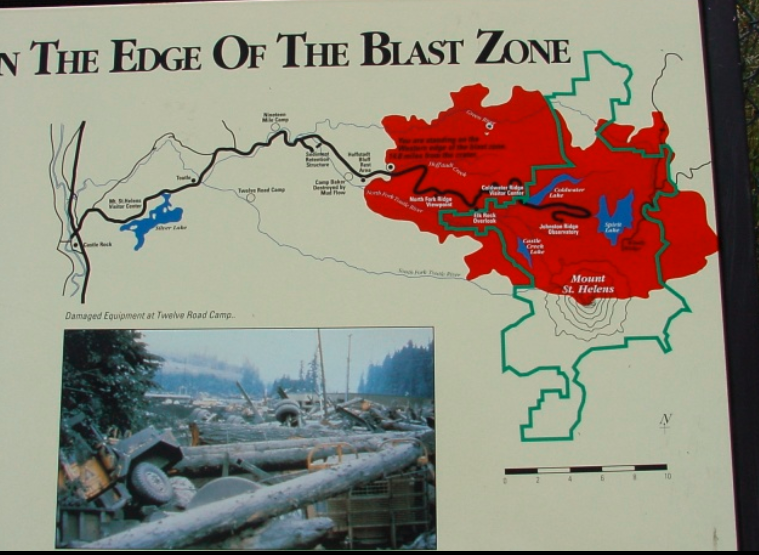

As you enter the monument, a sign on the side of a bridge shows the regiojn affected. The map showing the edge of the blast zone sends home the magnitude of the damage. in a matter of minutes, the landscape over a huge area was forever different.

In the blast area, he destruction was quite complete. What was forested land was now toothpicks. Trees for miles around the north of Mt St Helens were blown over like matchsticks, coming to rest in the direction of the shockwave and winds from the blast.

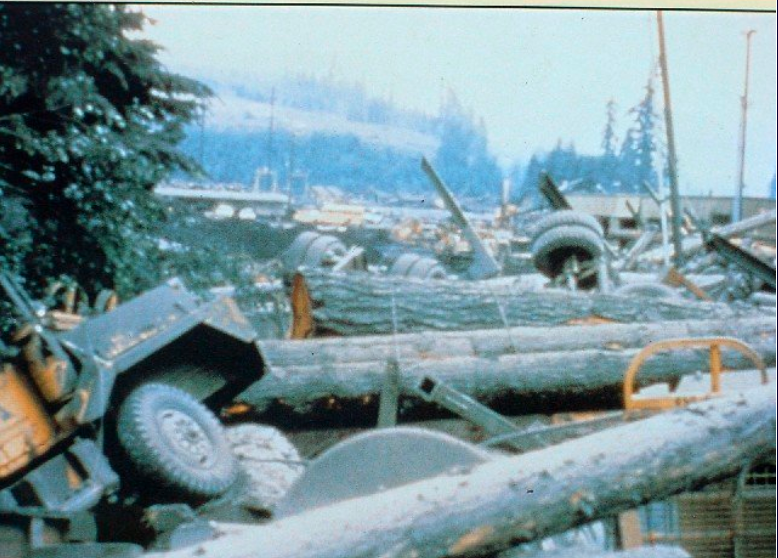

Weyerhaeuser, a timber company in the Northwest, owned much of the property that was damaged in the blast, and the various camps operating wound the Mountain were heavily damaged.

Recovery has been surprisingly quick. One of the side effects of having the trees removed is a great area for grasses and clovers… favorites of deer and caribou. This herd moved into the valleys around the volcano shortly after the grasses returned, and now remain there year-round. The river you see on the far side of the meadow changes its course every few years, as there is no bedrock for a firm channel… you can see the path it took a couple of years ago, now a dry river bed. This area was inundated by a massive, 300-foot high wall of mud, part of the massive landslide created when thousands of tons of glacial ice melted, suddenly finding themselves thousands of feet below the snow line, and covered in hot volcanic material.

The first Good View

At the head of the valley: the object that caused it all. Along the road to Johnston Ridge, which is across form the crater itself, there are several turnouts, this one, near Weyerhaeuser’s Forest Information Center, provides you with the first ‘good’ view of the young mountain

The view of the mountain is impressive and eerie at the same time. Trees for miles around are all the same age: young. The Old Growth that was there before the blast was knocked down, or scorched to death. Billions of board feet were recovered, but that didn’t even make a dent on what was wasted on the ground.

Recovery

As you get closer to the volcano, you can see how the slow progress of plant life has not fully made it to the mountains sides… the entire blast zone was sterilized: every plant, animal, and microbe was killed. Recovery is obvious, but slow.As you get closer to the volcano, you can see how the slow progress of plant life has not fully made it to the mountains sides… the entire blast zone was sterilized: every plant, animal, and microbe was killed. Recovery is obvious, but slow.

Hearty Plants come first

Mountain flowers are flourishing in the abundant sun. Normally, these plants struggle to get enough light, and are limited to patches of high mountain meadows.Mountain flowers are flourishing in the abundant sun. Normally, these plants struggle to get enough light, and are limited to patches of high mountain meadows.

Down with the hummocks

Throughout the first day of the eruption, a massive mudflow filled the valley with up to 600 feet of hot mud, trees, rocks, and ash, a slurry that took out homes and changed the Toutle river valley forever. Walking the trails in the valley gives you a first-hand view of the destruction, with uneven pockets of terrain freezing the scene for you.

It is beautiful and eerie at the same time.

Awesome beauty.

Psalm 104: Says “He touches the mountains and they smoke” Once a pocket of intense destruction, this place now shows the beauty of His handiwork.

he view from Johnston’s Ridge, which was renamed after the blast after a USGS geologist who had the unfortunate task of monitoring the equipment on the day of the blast, and who called his headquarters moments before the blast hit him. In some places, more than 100 feet of the top of the ridge was eroded away by the trees and boulders that passed by at over 300 miles per hour.

Johnston Ridge

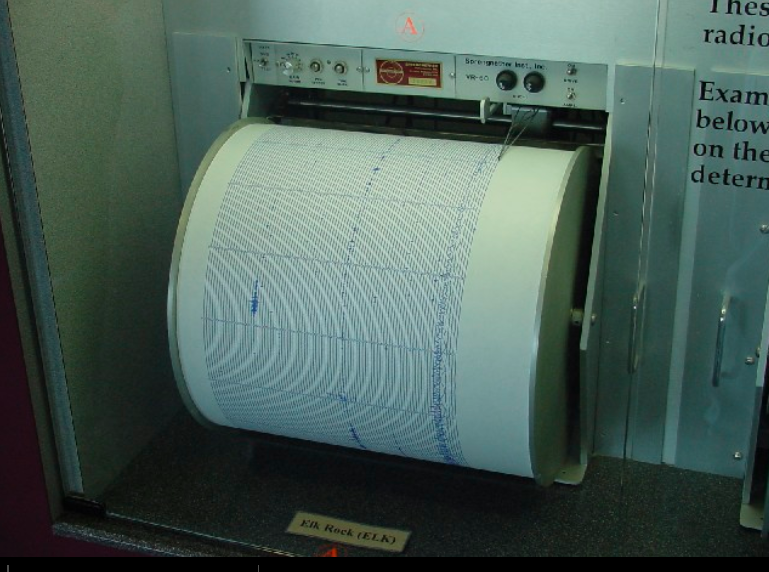

Named for the geologist who was on the ridge when The Mountain blew, the USGS and the US Forest Service run a Volcanic Observatory that is open to the public, allowing it to double as an information center. The new observatory on the Ridge completes a series of observatories that dot the road into the monument, providing quite a bit of information to those travelling to the Mountain.

Not Done Yet.

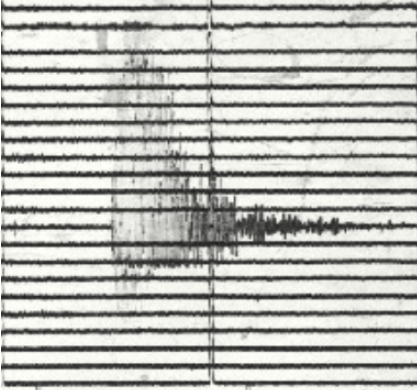

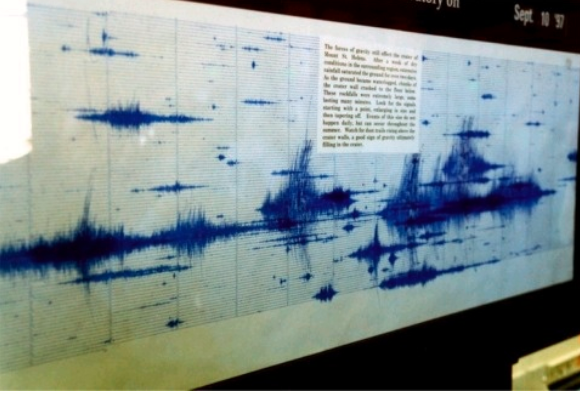

Shaking still happens! Earthquakes are still common on the Mountain, even 20 years later. A few days before I visited in 2000, they had a busy day on the ridge, which made for a pretty incredible graphic showing how active the Mountain still is.

While I was there, a small one happened in the crater…

Johnston Ridge provides a peek-a-boo view of Spirit Lake – or what is left of it. During the blast, the water was thrown more than 800 feet up the ridge behind the lake, and dumped 300+ feet of debris in its bed before the water, laden with blown-down trees, sloshed back in. Falling FAR shy of its previous beauty, the lake is actually recovering faster than scientists expected it would – which is a familiar statement at all of the talks about recovery in other areas as well.

This shot from ColdwaterRidge from a visit in 2002 shows the incredible amount of GREEN that can already be seen.

While Spirit Lake met its near-demise in the blast, Coldwater Lake got its birth.

Fish have already discovered the new lake, and it is quickly becoming a popular stop for fishermen.

Piles of rocks, ejected during the eruption and tossed over Johnston Ridge, are all over the place, reminders that this beautiful area had a violent birth.

Power.

this tree protrudes from the ground near Lewitt Overlook. it was blown through solid granite. it clearly shows the destructive force of the blast that shaped the area on an otherwise normal Sunday in May.

Recovery

The blast killed everything, even the bacteria in the dirt. Recovery has been surprisingly quick in geological terms, but slow and steady in real time. Every visit I make to The Mountain surprises me with more life, more growth, and more scenery, even trees in many places. Eventually, it will return to the forested region it was before the fateful day in May of 1980, and it will be lush and green as before.

Right about the time the mountain decides to wake up again.

Until then, I plan on returning, and watching as much of the recovery as I can first hand.